Rounding Errors

Because floating-point numbers have a limited number of digits, they cannot represent all real numbers accurately: when there are more digits than the format allows, the leftover ones are omitted - the number is rounded. There are three reasons why this can be necessary:

- Too many significant digits - The great advantage of floating point is that leading and trailing zeroes (within the range provided by the exponent) don’t need to be stored. But if, without those, there are still more digits than the significand can store, rounding becomes necessary. In other words, if your number simply requires more precision than the format can provide, you’ll have to sacrifice some of it, which is no big surprise. For example, with a floating point format that has 3 digits in the significand, 1000 does not require rounding, and neither does 10000 or 1110 - but 1001 will have to be rounded. With the large number of significand digits available in typical floating-point formats, this may seem to be a rarely encountered problem, but if you perform a sequence of calculations, especially multiplication and division, you can very quickly reach this point.

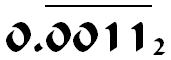

- Periodical digits - Any (irreducible) fraction where the denominator has a prime factor that does not occur in the base requires an infinite number of digits that repeat periodically after a certain point, and this can already happen for very simple fractions. For example, in decimal 1/4, 3/5 and 8/20 are finite, because 2 and 5 are the prime factors of 10. But 1/3 is not finite, nor is 2/3 or 1/7 or 5/6, because 3 and 7 are not factors of 10. Fractions with a prime factor of 5 in the denominator can be finite in base 10, but not in base 2 - the biggest source of confusion for most novice users of floating-point numbers.

- Non-rational numbers - Non-rational numbers cannot be represented as a regular fraction at all, and in positional notation (no matter what base) they require an infinite number of non-recurring digits.

Rounding modes

There are different methods to do rounding, and this can be very important in programming, because rounding can cause different problems in various contexts that can be addressed by using a better rounding mode. The most common rounding modes are:

- Rounding towards zero - simply truncate the extra digits. The simplest method, but it introduces larger errors than necessary as well as a bias towards zero when dealing with mainly positive or mainly negative numbers.

- Rounding half away from zero - if the truncated fraction is greater than or equal to half the base, increase the last remaining digit. This is the method generally taught in school and used by most people. It minimizes errors, but also introduces a bias (away from zero).

- Rounding half to even also known as banker’s rounding - if the truncated fraction is greater than half the base, increase the last remaining digit. If it is equal to half the base, increase the digit only if that produces an even result. This minimizes errors and bias, and is therefore preferred for bookkeeping.

Examples in base 10:

| Towards zero | Half away from zero | Half to even | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1.5 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| -1.6 | -1 | -2 | -2 |

| 2.6 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 2.5 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| -2.4 | -2 | -2 | -2 |

More rounding methods can be found at Wikipedia.

© Published at floating-point-gui.de under the Creative Commons Attribution License (BY)